On January 7, ICE Agent Jonathan Ross shot and killed Renee Good, a 37-year-old U.S. citizen, on the streets of Minneapolis. The Justice Department has refused to open a criminal investigation into the shooting, hastily declaring it an act of self-defense that does not warrant a criminal inquiry. But despite statements by administration officials to the contrary, there is more than enough for DOJ to investigate here. I know from experience.

For over a decade, I was a prosecutor in the Criminal Section of DOJ’s Civil Rights Division, the office dedicated to—and staffed with experts on—investigating and prosecuting officer-involved shootings and other uses of excessive force. From reviewing, investigating, and prosecuting law-enforcement misconduct cases, I know both whether and how DOJ, across administrations, would look into something like the Jan. 7 shooting.

I also know just how challenging such investigations can be and how difficult these cases are to prove. Prosecutors must first find that the force used was excessive as a matter of constitutional law. That means, in Fourth Amendment parlance, the force was an objectively unreasonable seizure. Prosecutors must prove this under a legal standard that explicitly allows “for the fact that…officers are often forced to make split-second judgments—in circumstances that are tense, uncertain, and rapidly evolving—about the amount of force that is necessary in a particular situation.” Graham v. Connor, 490 U.S. 386, 396-97 (1989).

And even if the force is excessive, prosecutors must also prove the agent’s intent. The law sets an exceptionally high bar here. Prosecutors must prove that the agent acted “willfully,” meaning that he must have had the specific intent to deprive someone of a constitutional right. As I and many other civil rights prosecutors have explained to juries in these cases, willfulness requires the agent to know what he is doing is wrong and decide to do it anyway, one of the most stringent mens rea requirements in criminal law. That standard permits prosecution of agents who purposefully or consciously choose to act in violation of the Constitution (not to mention in violation of their training and experience). But it precludes prosecution of agents who, no matter how unreasonable their use of force, nonetheless acted unknowingly, negligently, or in the good faith (but incorrect) belief that the force was necessary. One result of these requirements is that federal prosecutions for excessive force are typically brought only on the most unassailable evidence and are, in the grand scheme of things, relatively rare.

This legal framework is governed by 18 U.S.C. § 242, the statute DOJ uses to prosecute excessive force cases at the federal level. That provision makes it a crime when “[w]hoever, under color of any law, statute, ordinance, regulation, or custom, willfully subjects any person in any State, Territory, Commonwealth, Possession, or District to the deprivation of any rights, privileges, or immunities secured or protected by the Constitution or laws of the United States.” The statute, which dates to the post-Civil War Reconstruction Era, applies when any government official, including an immigration agent, willfully violates a person’s constitutional rights. The Civil Rights Division’s Criminal Section, often in partnership with U.S. Attorney Offices across the country, has used that statute to successfully prosecute cases like the Rodney King beating, the fatal shooting of Walter Scott, and the murder of George Floyd, among others.

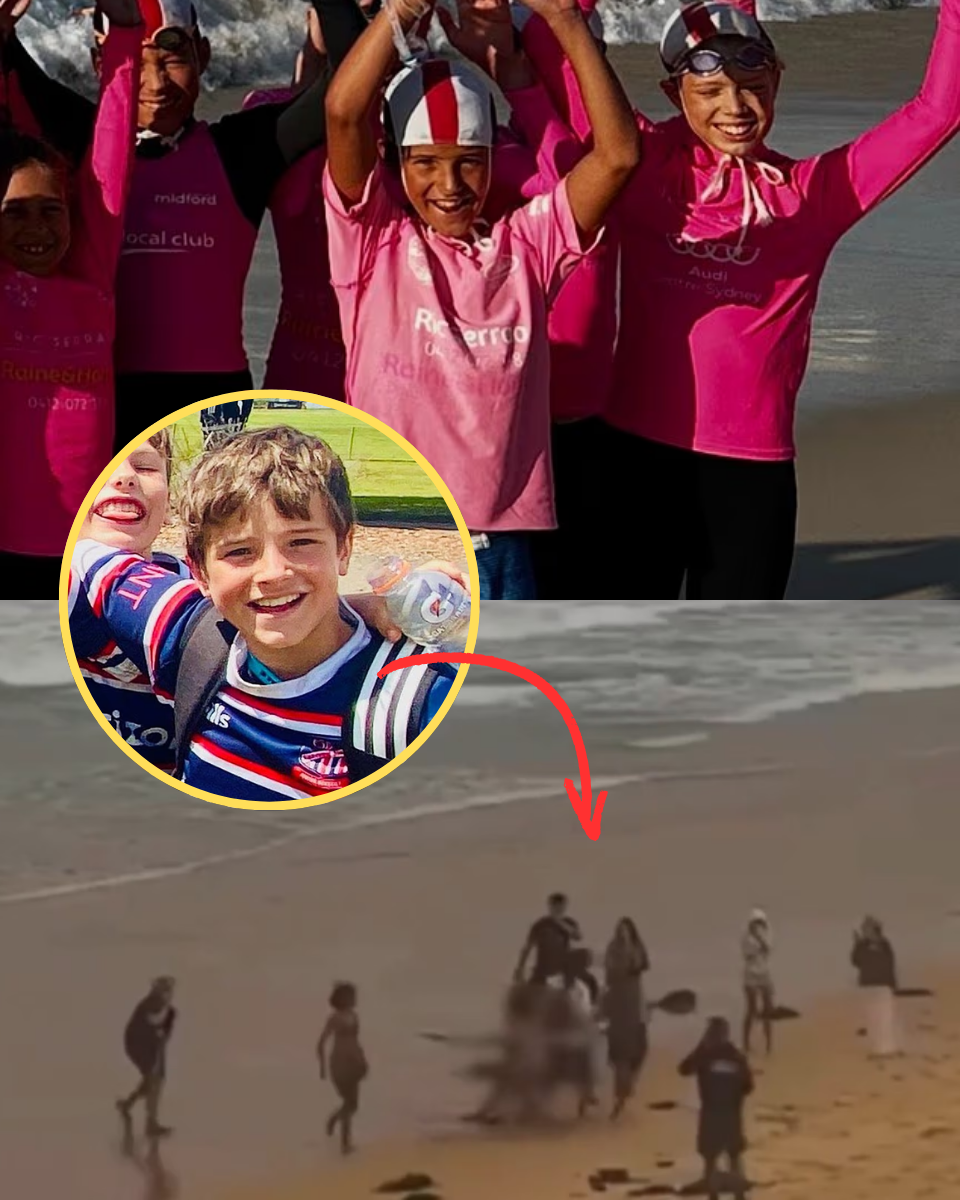

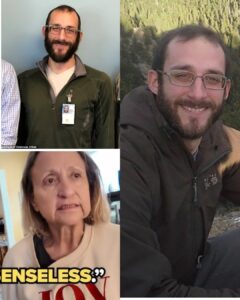

Since Good’s shooting, facts have incrementally emerged that point to both the excessiveness of Agent Ross’s use of force and to his intent. Exhaustive reporting has helped establish many of the circumstances surrounding the Jan. 7 shooting, including through a multi-angle, step-by-step analysis of the incident. It’s a good start in determining whether the force was unreasonable. The fact that agents had been able to pass by Good’s vehicle; that Good was clearly turning her steering wheel and vehicle away from the agents at the time shots were fired; that there was a notable gap between Agent Ross’s body and the vehicle, at least at the time of the second and third shots; that he was the only agent on the scene to even attempt to use any kind of force—all indicate that resorting to deadly force was not reasonable under the circumstances. Prosecutors would, of course, want to test, corroborate, and build on that evidence through, among other things, ballistics analysis, complete autopsy and medical reports, and witness accounts. Definitively establishing where the agent was positioned when he fired the shot that, according to an independent medical pathologist’s report, struck the left side of Good’s head and likely killed her, will be critical.

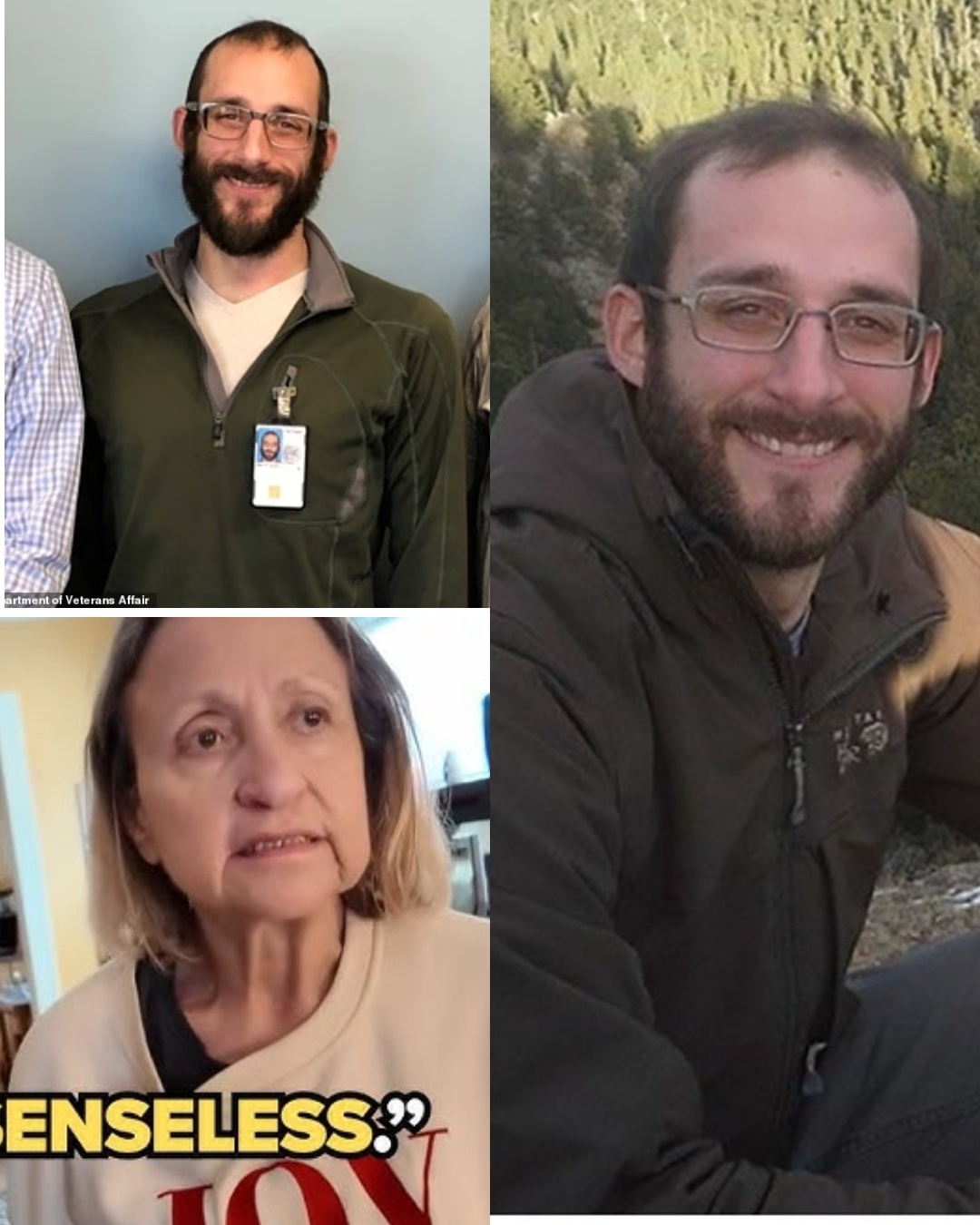

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():focal(749x0:751x2)/renee-good119-011926-573d8a33afe140eca3213327152295b9.jpg)

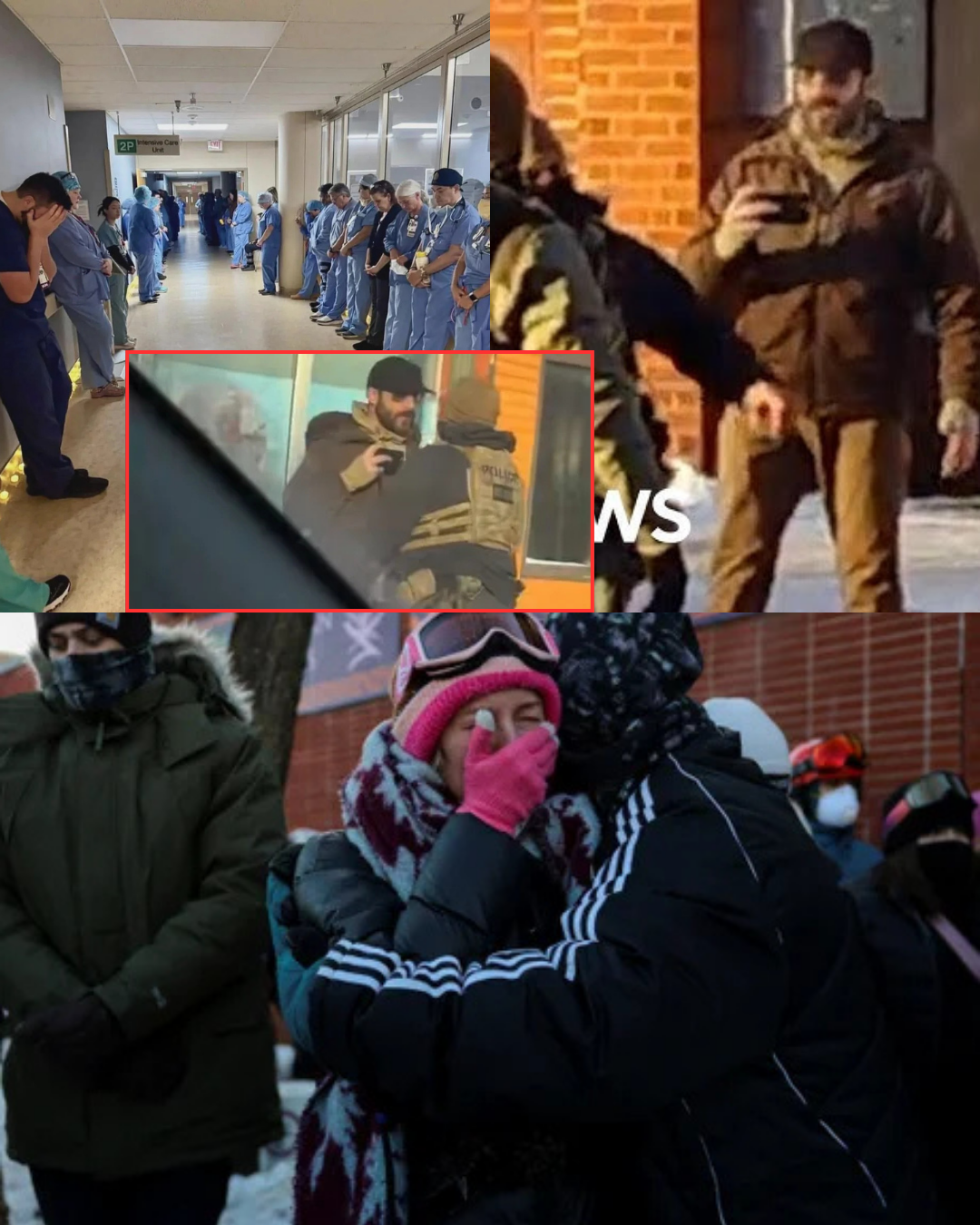

The more difficult question, as in so many of these cases, is one of intent. Prosecutors must prove the agent’s thinking and motivation. To this end, there is evidence that Agent Ross did not view Ms. Good as an imminent physical threat. Multiple videos show, for instance, that Agent Ross’s own vehicle was able to get around Ms. Good’s SUV, that he chose to walk around the front of Ms. Good’s vehicle (thereby exposing himself to possible harm, and against DHS policy) with one hand occupied by a cell phone, and that, just prior to the shooting, Ms. Good told the agents, “I’m pulling out.” Other evidence suggests that Agent Ross may have shot because he felt annoyed or disrespected by Ms. Good and her partner, rather than out of fear for his safety. The former are improper motivations that would support § 242’s willfulness prong. From the outset, for example, videos show that Ms. Good and her partner stopped their SUV in the street and honked the horn repeatedly in apparent protest of the ICE agents. Additionally—and courtesy of the agent’s own cellphone video, which importantly provides a view of the incident from his perspective—we can hear Ms. Good say, “That’s fine dude, I’m not mad at you,” and her partner sarcastically tell Agent Ross to “go get yourself some lunch, big boy.” Perhaps giving a window into his irritation at these remarks or Ms. Good’s attempt to drive away, Agent Ross muttered after firing his weapon at her, “f*cking b*tch.” He walked away from Ms. Good’s SUV, which had by that point crashed into a parked vehicle (a clear sign that Ms. Good was injured or dead), and gestured to someone else to “call 911.”

Together, these facts are more than enough to show the allegation that Agent Ross willfully used excessive force when he shot Ms. Good is a serious one. And because that allegation, if proven, would constitute a violation of federal law, it is wholly appropriate to open a formal investigation into the shooting. (Indeed, it is no wonder that an initial FBI review reportedly concluded that opening an investigation was justified.)

Based on my experience, further investigation should build on the early indications of Agent Ross’s intent. That issue will almost certainly boil down to whether evidence shows the agent actually did fear for his (or others’) safety, or whether he unlawfully acted out of anger, in retaliation, or to stop Ms. Good as she drove away. On the last point: to the extent Agent Ross was taught even the most basic law governing uses of force, he was likely told that the use of deadly force to prevent someone who poses no immediate threat from escaping is constitutionally unreasonable. Tennessee v. Garner, 471 U.S. 1, 11 (1985).

What specifically would investigators look for? Several categories of evidence are relevant here, and the list below is far from exhaustive:

Radio traffic and witness accounts that might capture, in real time, how Agent Ross experienced the incident and in particular any comments he made before, during, and after the shooting that could provide a window into his mindset;

Medical records for Agent Ross, which, in addition to bearing on allegations that Ross was hit by Ms. Good’s vehicle and suffered internal bleeding, may contain the agent’s account of whether and how he received any injuries;

Witness accounts, particularly from other agents on the scene who experienced the incident from a similar vantage point and who could speak to whether they viewed Ms. Good as a physical threat;

Routine incident and use-of-force reports from Agent Ross and others containing their accounts of the shooting, which could reveal inconsistencies between early and later accounts;

Training records, to determine whether Agent Ross’s actions were consistent with or in contravention of how he was taught and trained; and

Other personnel records to identify prior uses of force or displays of his firearm and any resulting remediation or discipline that might have put Agent Ross on notice about unlawful force.

None of these investigative steps remotely resembles how this administration has approached the shooting. In the wake of Ms. Good’s death, administration officials rushed to judgment, suggesting that the agent shot Ms. Good in self defense and condemning Ms. Good’s actions as “domestic terrorism.” Less than three hours after the incident, DHS tweeted that Ms. Good had “weaponized her vehicle” and “attempt[ed] to run over our law enforcement officers in an attempt to kill them.” With no investigation whatsoever, DHS apparently concluded that the agent had “fired defensive shots” out of fear for his and others’ lives. In line with these premature conclusions, the administration has refused to seriously examine what happened. On Jan. 13, DOJ Deputy Attorney General Todd Blanche declared that there was “no basis for a criminal civil rights investigation.” Blanche has since reiterated his belief that it is not “appropriate to investigate” the shooting and has definitively stated that DOJ is “not investigating.”

But only after completing a fair and thorough investigation involving the steps described above (and likely many others) would prosecutors be able to decide whether to pursue criminal charges—which requires that they believe the “conduct constitutes a federal offense, and that the admissible evidence will probably be sufficient to obtain and sustain a conviction” by proof beyond a reasonable doubt. This process—from initial allegation through investigation to charging decision—is highly important. It supports the legitimacy of our criminal justice system by allowing charges to be brought only when supported by evidence obtained through an unbiased investigation. It seeks to spare crime victims the heartache of acquittals or dismissals for insufficient evidence. It benefits officers, too. The process ensures that any decision to decline charges is credibly based on a thorough review, rather than a political whim. And finally, a careful investigation serves an important social good by helping ensure that the rules around the use of force are carefully followed and signaling to officers that, this administration’s false assurances aside, they do not have absolute immunity for criminal conduct.

Perhaps an investigation would ultimately support the administration’s predetermination that the Jan. 7 shooting does not merit prosecution. Perhaps not. Additional evidence is sure to emerge that could cut either for or against seeking charges. But it is absolutely clear that the evidence at this point is more than sufficient to justify opening a criminal investigation into the agent’s conduct—a step that would be consistent with decades of DOJ practice and, until recently, would have been considered largely unremarkable.